Bret Harte

John W. Pinkerton

oldjwpinkerton@gmail.com

Bret Harte is an American writer one seldom hears anyone mention---for better or worse; however, when

I was teaching high school English, I always liked reading selections by Harte to my classes. On my own, I’ve read a lot of his works: they’re a little in your face at times. Some remind me of situation comedies…a little broad---but entertaining.

I think of Harte as the poor man’s Mark Twain…not quite as good of a writer, but his subject matter and time period were similar to Twain’s and at one time they were friends.

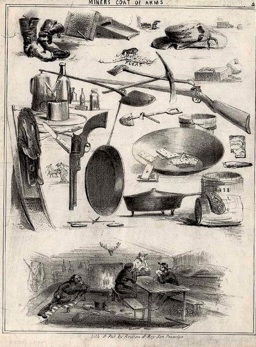

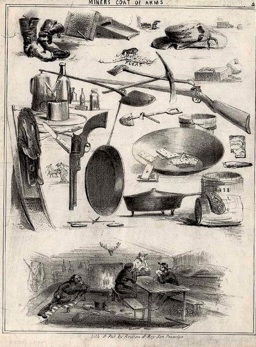

Harte is mainly remembered for his stories set in the California Gold Rush which meant his stories featured characters such as miners, and gamblers, and other interesting characters.

Harte had a 40 year career as a writer: poetry, lectures, plays, editorials, magazine articles, book reviews and, of course, his works of fiction.

As a teacher, I always hoped the authors featured in my courses had highly interesting lives---Harte I’d say had an interesting but not fascinating life.

Like a lot of writers, Harte was a big reader as a youth. He was born in Albany, New York, in 1832, and his father was Bernard, an Orthodox Jew who was one of the founders of the New York Stock Exchange.

Apparently, he was adventurous and in 1853 he moved to California where he worked as a miner, schoolmaster, and journalist. As a journalist he began to hit his stride.

While working as an assistant editor for the Northern Californian he wrote an editorial detailing the horrors of the massacre of the Wiyots at Tuluwat where between 80 and 200 men, women and children were slain. Some folks didn’t care for his editorial and threatened him causing him to move on to San Francisco where he became an editor of the Golden Era, a newspaper, in 1857 where he published his first poetry and his first prose piece, “A Trip Up the Coast.” He was hired as the editor in 1860 and attempted to turn it into a literary publication which caught the favorable attention of Mark Twain. Here he wrote parodies and satires of other writers which Twain praised. He started a new literary magazine in 1864, The Californian. He then became editor of the Overland Monthly, another literary magazine. In the second issue, he published “The Luck of Roaring Camp,” probably his best known short story, and it brought him national fame.

While the iron was hot, he moved back East and demanded a high salary at the Atlantic Monthly, but soon interest in his writing waned, and he fell on hard time. Desperate, he sought a consularship to Krenfel, Germany. Mark Twain, with whom he had had a falling out, tried to block him from this position: "Harte is a liar, a thief, a swindler, a snob, a sot, a sponge, a coward, a Jeremy Diddler, he is brim full of treachery....”

Twain’s letter apparently was pretty effective, but Harte did get a different consul position, Glasgow. In his latter years, Harte was able to continue to write stories most of which were first rate.

He died in Camberley, England in 1902.

Enough about the man: what about his writing. Well, I’ve included some opening paragraphs from several of his short stories:

The Luck of Roaring Camp

There was commotion in Roaring Camp. It could not have been a fight, for in 1850 that was not novel enough to have called together the entire settlement.

The ditches and claims were not only deserted, but "Tuttle's grocery" had contributed its gamblers, who, it will be remembered, calmly continued their game the day that French Pete and Kanaka Joe shot each other to death over the bar in the front room. The whole camp was collected before a rude cabin on the outer edge of the clearing. Conversation was carried on in a low tone, but the name of a woman was frequently repeated. It was a name familiar enough in the camp,--"Cherokee Sal."

The Outcast of Poker Flat

As Mr. John Oakhurst, gambler, stepped into the main street of Poker Flat on the morning of the 23d of November, 1850, he was conscious of a change in its moral atmosphere since the preceding night. Two or three men, conversing earnestly together, ceased as he approached, and exchanged significant glances. There was a Sabbath lull in the air, which, in a settlement unused to Sabbath influences, looked ominous.

A Yellow Dog

I never knew why in the Western States of America a yellow dog should be proverbially considered the acme of canine degradation and incompetency, nor why the possession of one should seriously affect the social standing of its possessor. But the fact being established, I think we accepted it at Rattlers Ridge without question. The matter of ownership was more difficult to settle; and although the dog I have in my mind at the present writing attached himself impartially and equally to everyone in camp, no one ventured to exclusively claim him; while, after the perpetration of any canine atrocity, everybody repudiated him with indecent haste.

A Convert of the Mission

The largest tent of the Tasajara camp meeting was crowded to its utmost extent. The excitement of that dense mass was at its highest pitch. The Reverend Stephen Masterton, the single erect, passionate figure of that confused medley of kneeling worshipers, had reached the culminating pitch of his irresistible exhortatory power. Sighs and groans were beginning to respond to his appeals, when the reverend brother was seen to lurch heavily forward and fall to the ground.

A Drift from Redwood Camp

They had all known him as a shiftless, worthless creature. From the time he first entered Redwood Camp, carrying his entire effects in a red handkerchief on the

end of a long-handled shovel, until he lazily drifted out of it on a plank in the terrible inundation of '56, they never expected anything better of him. In a community of strong men with sullen virtues and charmingly fascinating vices, he was tolerated as possessing neither--not even rising by any dominant human weakness or ludicrous quality to the importance of a butt. In the dramatis personae of Redwood Camp he was a simple "super"--who had only passive, speechless roles in those fierce dramas that were sometimes unrolled beneath its green-curtained pines. Nameless and penniless, he was overlooked by the census and ignored by the tax collector, while in a hotly-contested election for sheriff, when even the head-boards of the scant cemetery were consulted to fill the poll-lists, it was discovered that neither candidate had thought fit to avail himself of his actual vote. He was debarred the rude heraldry of a nickname of achievement, and in a camp made up of "Euchre Bills," "Poker Dicks," "Profane Pete," and "Snap-shot Harry," was known vaguely as "him," "Skeesicks," or "that coot." It was remembered long after, with a feeling of superstition, that he had never even met with the dignity of an accident, nor received the fleeting honor of a chance shot meant for somebody else in any of the liberal and broadly comprehensive encounters which distinguished the camp. And the inundation that finally carried him out of it was partly anticipated by his passive incompetency, for while the others escaped--or were drowned in escaping--he calmly floated off on his plank without an opposing effort.

Uncle Jim and Uncle Billy

They were partners. The avuncular title was bestowed on them by Cedar Camp, possibly in recognition of a certain matured good humor, quite distinct from the spasmodic exuberant spirits of its other members, and possibly from what, to its

youthful sense, seemed their advanced ages—which must have been at least forty! They had also set habits even in their improvidence, lost incalculable and unpayable sums to each other over euchre regularly every evening, and inspected their sluice-boxes punctually every Saturday for repairs—which they never made. They even got to resemble each other, after the fashion of old married couples, or, rather, as in matrimonial partnerships, were subject to the domination of the stronger character; although in their case it is to be feared that it was the feminine Uncle Billy—enthusiastic, imaginative, and loquacious—who swayed the masculine, steady-going, and practical Uncle Jim. They had lived in the camp since its foundation in 1849; there seemed to be no reason why they should not remain there until its inevitable evolution into a mining-town. The younger members might leave through restless ambition or a desire for change or novelty; they were subject to no such trifling mutation. Yet Cedar Camp was surprised one day to hear that Uncle Billy was going away.

I hope these samples have whetted your appetite for Harte; however, I suspect it’s just me.

If you’re interested in reading any of his short stories on line, go to Bret Harte.

enough