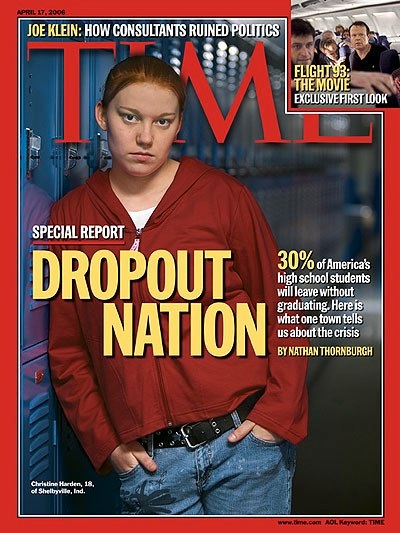

Dropouts and Graduates

Hammond, President and CEO of the Texas Association of Business, discussed the recent study of young people who did not progress beyond the eighth grade of school. According to this study of all Texas students who were eighth graders in 2001, 27% did not graduate high school in four years. Only 19% of that class completed any type of post-secondary education.

“I think this one does a good job, because there is very little wiggle room. You are either successful in getting students a high school diploma and post-secondary training, or you are not. This study shows we are not.

“If our children are going to be successful in life, the education community is going to have to step up and do better. The legislature, school boards, and administrators are going to have to hold the system accountable.”

The statistics are bad enough. Unfortunately, Hammond’s conclusions are even worse. They fly in the face of the truism that you can lead a horse to water, but you cannot make him drink.

Metaphorically, students are led to the water or schools by the truancy laws. Once there, however, some cannot be made to even try to learn enough to graduate much less be interested in additional academic or vocational training after a high school diploma.

With that in mind, laying the blame for the poor school completion rates on the school system and educators is a bit harsh.

My granddaughter, Emily, teaches history and geography at Anderson High School in Austin. She will not go as far as I do in defense of the schools.

She believes more students could be motivated to learn and progress if teachers were allowed to make their classes more fun and interesting by responding to the students’ desires and interests. The teachers are hide bound, however, by what she calls the road maps established by the administrators for their teachers. (Anderson does not use CSCOPE but follows the curricular developed in house.)

Emily’s description of several hours in her class gives some credence to Hammond’s opinion. The rigid teaching methods required by TEKS and STAAR make schools a dull place to spend eight hours every day. It does not, however, address the other major factor in this discussion. What about family responsibility in the matter?

I never told my children that they had to go to college, but all four of them are college graduates. One is a lawyer, one an oil drilling supply company executive, one a bank vice-president, and one a CPA/CIA. I recently asked each of them independently, “Why did you go to college?” The four answers were identical, “Because I knew it was expected of me.”

So here’s the perspective.

If a student without an attitude something like that of my children is forced into school by a truant officer, what teaching methods and practices can steer him toward a college mortarboard or anything similar?

enough