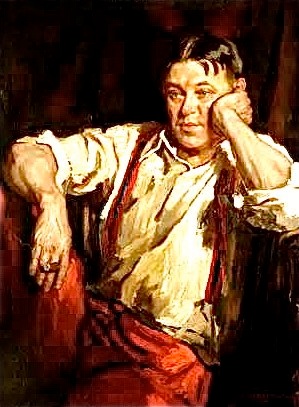

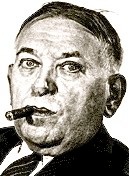

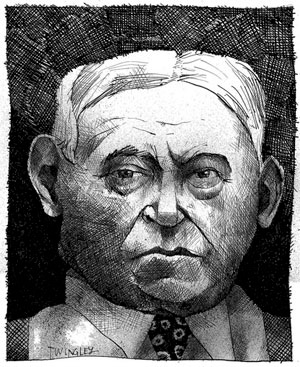

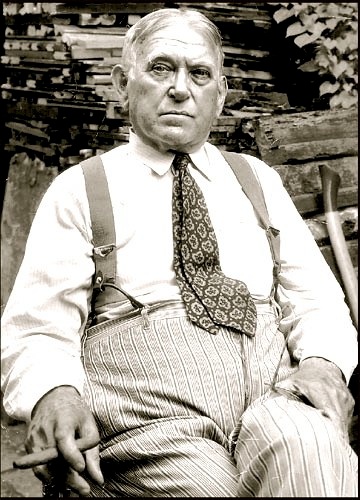

H. L. Mencken

Folks, we’ve got to quit dismissing people from our past who by today’s standards would be considered racist.

The other day a friend of mine sent me a quote from H. L. Mencken. The email reminded me of how much I have admired the writing of Mencken through the years. My first thought when I saw his name was, “Why don’t I hear more about Mencken today?”

After doing a little research on Mencken on the internet, I was confronted by his racism. Perhaps this is the reason he’s pretty well been ignored in recent years.

Mencken was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1880 and died in Baltimore in 1956. He began life in the Union Square neighborhood. He described his childhood years as “placid, secure, uneventful, and happy.” After reading Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, he decided to become a writer himself. He read Thackeray, Addison, Steele, Pope, Swift, Johnson, Shakespeare, Kipling, and Thomas Huxley. He was interested in photogaphy and had his own chemistry laboratory. He graduated as valedictorian from the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute and spent the next three years in his father’s cigar factory. Still determined to become a writer, he took a class in writing from the Cosmopolitan University, one of the country’s first correspondence schools. In 1899, after his father’s death, he was hired by the Baltimore Morning Herald newspaper as a a part-timer. After a few months, he became a full-time reporter. After six years, he moved on to The Baltimore American and then The Baltimore Sun. He continued to write for the Sun until he had a stroke in 1948. It was his editorials and opinion pieces chiefly that made him a memorable writer in our country’s history. While writing the editorials, he also wrote short stories, a novel, literary criticism, and poetry.

Why would he be considered racist? Although he had no apparent animosity toward Blacks, he considered them forever hopeless. He wasn’t mean spirited in his beliefs and spoke vehemently against lynchings. As for Jews, he wasn’t exactly respectful of Jews describing them as, “...the most unpleasant race ever heard of.” However, he described Adolf Hitler as a buffoon and compared him to a Ku Klux Klan member and attacked President Franklin D. Roosevelt for refusing to admit Jewish refugees into the United States: “Why shouldn’t the United States take a couple hundred thousand of them {Jewish refugees}, or even all of them?”

The truth is that Mencken was more of an elitist than a racist. His disdain was directed at many subjects, not just the weak and downtrodden. President Roosevelt got an earful. Mencken believed that every community produced a few people of clear superiority. He believed that superior individuals are distinguished by their will and personal achievement, not by race or birth.

Mencken exhibited several characteristics which I admire: a sense of humor about the world and himself--he often called for folks to hold his opinions lightly; a brilliant mind continually active and capable of change--take for example his views on race and in a lighter vein his views on marriage which changed from considering marriage “the end of hope” to a happy marriage of five years which tragically ended by the untimely death of his beloved Sara.

I’m not asking the reader to ignore Mencken’s racist beliefs but rather to consider them in the context of his time and his personal achievements.

The best known of Mencken’s works is The American Language, a work on the American language, a language he described as more colorful, vivid, and creative than the British version. He wrote three notable biographical works: Happy Days (1940), Newspaper Days (1941), and Heathen Days (1943).

There are many more accomplishments by Mencken that I could list, but I suspect I would be gilding the lily. The following quotes should give you a little insight into who H. L. Mencken was and why he should be admired.

Mencken was suspicious of our democracy:

Every decent man is ashamed of the government he lives under.

I believe that all government is evil, and that trying to improve it is largely a waste of time.

It is inaccurate to say that I hate everything. I am strongly in favor of common sense, common honesty, and common decency. This makes me forever ineligible for public office.

The government consists of a gang of men exactly like you and me. They have, taking one with another, no special talent for the business of government; they have only a talent for getting and holding office.

Under democracy one party always devotes its chief energies to trying to prove that the other party is unfit to rule - and both commonly succeed, and are right.

As democracy is perfected, the office of the President represents, more and more closely, the inner soul of the people. On some great and glorious day, the plain folks of the land will reach their heart's desire at last and the White House will be occupied by a downright fool and complete narcissistic moron.

Mencken is quick wit resulted in some pithy definitions.

A celebrity is one who is known to many persons he is glad he doesn't know.

A cynic is a man who, when he smells flowers, looks around for a coffin.

A judge is a law student who marks his own examination papers.

Love is the triumph of imagination over intelligence.

Puritanism: The haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.

Conscience is a mother-in-law whose visit never ends.

He was a keen observer of human nature:

Any man who afflicts the human race with ideas must be prepared to see them misunderstood.

Injustice is relatively easy to bear; what stings is justice.

It is even harder for the average ape to believe that he has descended from man.

It is the dull man who is always sure, and the sure man who is always dull.

Men are the only animals that devote themselves, day in and day out, to making one another unhappy.

My guess is that well over 80 percent of the human race goes without having a single original thought.

Nobody ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the American public.

The older I grow the more I distrust the familiar doctrine that age brings wisdom.

There is always a well-known solution to every human problem--neat, plausible, and wrong.

Mencken was not a religious man:

Say what you will about the Ten Commandments, you must always come back to the pleasant fact that there are only ten of them.

I suppose the reason I’ve written this essay on Mencken is because I admire him. I admire the brilliance of his mind, the flexibility of his thoughts, the humor of his words, his self-deprecation, and his enduring insight into the human condition.

enough