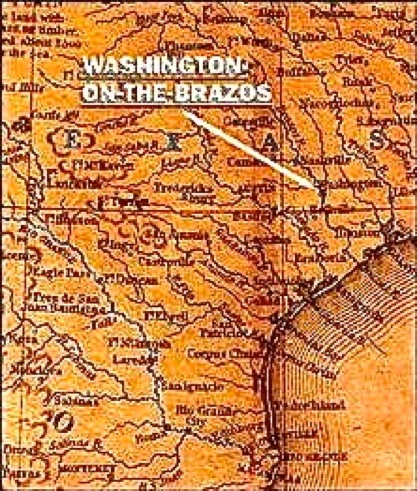

LaBahia/Washington

Some important people were missing from the accolades at last week’s birthday party for the Republic of Texas. Those were the original residents of the Republic.

American Indians who roamed the area long before Moses and Stephen F. Austin were born established the site where Texas became Texas. These nomads found the easiest route for their north and south wanderings in the area was to cross the Brazos River a mile down river from its junction with the Navasota River. Crossing one river here instead of two also allowed them to follow a trail along ridge lines that crossed no other live streams.

When the Spanish and French explorers began traveling the area, they followed the same route and began to call it the La Bahia trail. By this time, the heavy traffic of the Indians and animals had worn the banks on both sides of the Brazos so much that the La Bahia crossing was also easier than elsewhere.

That is why the La Bahia trail became the route for some of the Old Three Hundred funneling into the area the Austins had selected for their settlement. Some of those first Anglo settlers stopped on the West side of the Brazos and began building primitive homes. As the number of residents staying at the river grew, they began to call their settlement La Bahia.

By the end of 1821, Andrew Robinson, one of the first residents of La Bahia, was operating a ferry to cross the river. Within ten years, he asked Patsy and John W. Hall, his daughter and son-in-law, to join in his business, as he was also operating a boarding house that offered, according to an advertisement, “entertainment.”

Hall quickly recognized the commercial potential of the area and organized a partnership that surveyed a site on Robinson and Hall land along the river. The town was platted in a traditional square grid divided into 92 blocks 300 feet square. Each block contained 12 lots. The streets were named Main, Ferry, Market, Austin, Water, etc.

Asa Hoxey, one of Hall’s new partners, suggested that the porpoised settlement be named Washington after his hometown in Georgia. The suggestion was accepted and La Bahia was renamed Washington indirectly in honor of the Father of the United States.

When lots began being sold in Washington, the La Bahia ferry landing had already become the final port for flat bottomed steamers coming up the river from Galveston. This combination of a ferry landing and a sea port resulted in a rapid growth of the town.

By 1836, it was the largest and most important commercial enclave West of Galveston. The Washington streets were lined with accommodations for doctors, lawyers, merchants, boarding house operators, blacksmiths, saloon keepers, barbers, and others. It became the County Seat of Washington County, which then covered an area now divided into six counties.

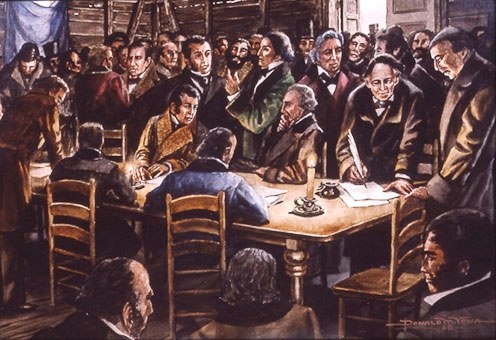

In February, 1836, the men gathered at Stephen F. Austin’s headquarters at San Felipe became concerned about the Mexican troops advancing toward them from San Antonio. Some merchants in Washington heard of these concerns and offered to provide a building in their community for a constitutional convention.

The delegates accepted the offer and arrived in Washington on a bitterly cold March 1. The so called Constitution Hall they found, however, was not what had been expected. They were ushered into an unfinished building without doors or windows. Cloth had been stretched over some window openings, but that provided little protection from the cold.

Living accommodations for the delegates were not much better. William Fairfax Gray, an observer at the convention, noted in his diary that he stayed in a boarding house in which “the host’s wife and children and about thirty lodgers all slept in the same apartment, some in beds, some on cots, but the greatest part on the floor.”

The food was of equal quality. Gray noted, “Supper consisted of fried pork and coarse corn bread, and miserable coffee.” He concluded that Washington is “a rare place to hold a national convention in. They will have to leave it promptly to avoid starvation.”

The men and women of those days were of a hardier stock than generally found today. They took up the task, produced and signed a Declaration of Independence from Mexico the next day and then drafted the Constitution of the Republic of Texas.

Washington continued to grow and prosper after those momentous days in 1836. It was the capitol of the Republic of Texas twice and the County Seat of Washington County. On some days three steamers that could carry 300 bales of cotton each were docked at the La Bahia ferry. Unfortunately, however, the city fathers refused an offer to bring the expanding railroad through town.

As the railroad on the other side of the Brazos began to replace the river boats for both passengers and produce, Washington began a slow decline. Most of the few buildings remaining in 1912 were destroyed by a fire and today nothing remains of the original town.

So here’s the perspective.

Where Texas became Texas is now marked by a solitary stone monument erected with donations from school children and a second replica of the crude building that served as the Constitutional Hall.

What was once La Bahia/Washington is now called Washington-on-the-Brazos, possibly to distinguish it from Washington-on-the-Potomac.

A small settlement that locals call Old Washington has been established just outside the bounds of LaBahia/Washington. It consists of a few empty buildings, a restaurant, and a U.S. Post Office serving 765 customers.

The trail blazed by the Indians and Spanish and French explorers is now a paved, scenic historic highway--FM 390.

When traveling that trail where moccasins led the way for European boots, let’s remember all who made Texas, Texas.

enough