The Last Chivalry

Chivalry has faded into antiquity. Some under the age of 70 have not even heard the word.

This medieval knightly system with its religious, moral, and social code combined the qualities expected of courage, honor, courtesy, justice, and a readiness to help the weak.

The code was followed to a certain extent by European armies into the 20th Century. Unfortunately, the last act of chivalry occurred on Dec. 20, 1943, in the skies over Germany.

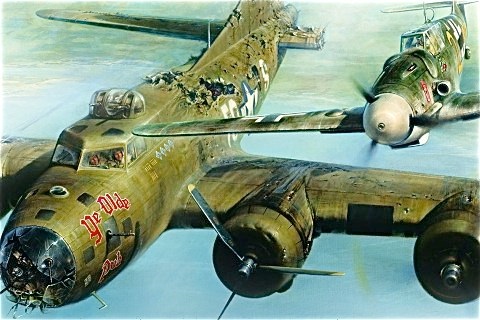

As the bomber did not have the protection of other planes, Franz knew the best attack was against the sole gunner in the tail. As he began his run against that position, he was surprised that he was not receiving fire. Getting closer, he noticed that most of the plane’s left stabilizer and much of the rudder were missing.

Then he noticed that the tail turret was in pieces and the remaining plexiglass was covered in frozen blood. Even closer and he could see Hugh “Ecky” Eckenode slumped dead over his twin 50 calibre machine guns.

Franz then pulled a bit higher and could see that only the top turret was manned. Bertrand “Frenchy” Coulombe had his guns trained on the Messerschmidt but could not fire because the tubes and mechanisms were still frozen from the high altitude of the bombing run.

Although he did not know that Alex “Russian” Yelesanko, the right waist gunner, was writhing in pain from his leg that was almost blown off and that his fellow crew men were trying to thaw the morphine syringes with their bare hands so they could provide some relief, Franz realized that this was a plane in real distress.

Then he recalled his first combat tour. In Africa in the Spring of 1942, Lieutenant Gunther Roedel advised Franz and his squadron mates that, “Every single time you go up, you’ll be outnumbered. Those odds may want to make a man fight dirty to survive. But let what I’m about to say to you act as a warning. Honor is everything here. If I ever see or hear of you shooting at a man in a parachute, I will shoot you down myself. You follow the rules of war for you, not for your enemy. You fight by rules to keep your humanity.”

With that advice ringing in his ears, Franz imagined men floating in parachutes. So he pulled up for his left wing to overhang the four motor’s right wing. He got Charlie’s attention and motioned downward for him to land. Charlie shook his head, “No!” So Franz motioned a right turn, hoping that Charlie would follow him and head for Sweden, a neutral country.

Charlie did not understand what he meant, but would not have gone there anyway. In a briefing by Colonel Maurice “Mighty Mo” Preston shortly after his arrival in England, the colonel stated that he hated the idea of safe havens. He added, “If you have power to get to Sweden, you have power to try to get back to England.” He then added that after the war he would court-martial any crew that had fled to a neutral country.

By this time the two planes were approaching the “Atlantic Wall,” the German coastline that was heavily fortified with anti-aircraft guns manned by the best gunners in Germany. Franz knew that the plane flying so low and slow on his left would not have a chance. Its only chance of survival was for him to escort it.

So he veered a bit right so that the full silhouette of his 109 would be recognized by the gunners as a German fighter.

On the ground, the gunners could not understand what they were watching. They did not know whether the bomber was one of those captured by the Luftwaffe to use for training or whether it was an enemy under one of their own waiting for a kill.

In any event, the gunners were ordered not to fire for fear of downing the 106. Charlie and Franz passed over the line of defense in formation and not a round was fired.

After Franz escorted Charlie beyond the line of sight from shore, he dipped his wings to Charlie, gave him a salute (the Nazi airmen continued to use the salute inherited from the knights and crusaders of raising the fighting arm to the brim of the visor to show that it was not armed instead of the stiff-armed Heil Hitler salute) and returned to Germany over a different area of the Atlantic Wall.

Back home, if he had told what he did, he would have been executed.

Meanwhile, by means no one can understand, Charlie limped back to England, just high enough to avoid obstacles. At the first landing strip available, the crew cranked the landing gear down by hand as there was no longer a hydraulic system and Charlie made an almost perfect landing.

As Charlie was making his after action report and talking about the problems of keeping the plane in the air, this conversation occurred:

“Why didn’t you hit the silk over Germany?”

“Sir, I had a man who was too injured to jump.”

“So you and your crew stayed for just one man?”

“Yes, sir. It was that simple.”

Charlie’s report was classified SECRET by 8th Air Force and he and his crew were ordered not to talk about it with anyone. The higher ups were concerned that the story about Franz not shooting the fortress down might result in other crews in similar circumstances not firing to protect themselves in the belief that other German pilots would act like Franz.

Franz ended WWII as one of Germany’s top aces. He was shot down six times. Three times he bailed out; three times he crash landed and survived all six.

He flew over the Atlantic Wall one more time. In 1953, long after the guns had fallen silent, he and his wife flew over the line in an airliner to their new home in Canada.

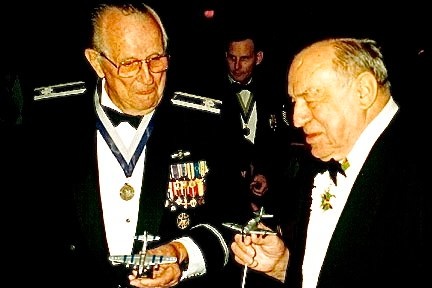

Franz died in March, 2008, and Charlie joined him seven months later.

Just after Franz died, and six months before Charlie’s death, the Air Force reviewed Charlie’s account of the encounter and awarded him the nation’s second highest medal for valor--the air Force Cross. The other members of his crew were awarded the Silver Star--one in person and eight posthumously.

A book that Franz gave Charlie bears the notation:

“In 1940, I lost my only brother as a night fighter. On the 20th of December, four days before Christmas, I had the chance to save a B-17 bomber from her destruction, a plane so badly damaged it was a wonder that she was still flying. The pilot, Charlie Brown, is for me, as precious as my brother.

Thanks Charlie,

Your brother, Franz”

So here’s the perspective.

Enough said.

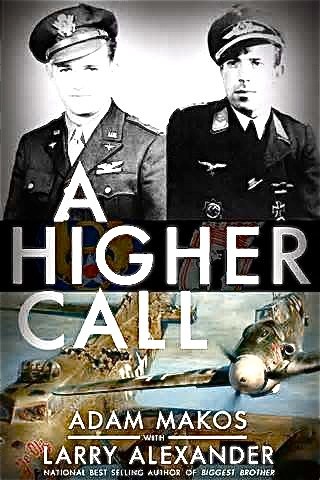

The full story can be found in Adam Makos’ book, A Higher Call.

enough