Time Marches On

When real time news began hitting radios and TVs in homes across the land in 1951, “The March of Time” reels were retired to the archives to rest with the hard copy descriptions of history.

Whether recorded on antique movie reels or modern digital chips, history was and is marching on. This is aptly illustrated by the changing times in Texas politics.

The state constitution was adopted in 1876. It was the seventh in the state’s history and is one of the longest in the country. In the century and a half of its existence, voters have been asked to vote on 662 amendments; 483 of them have been approved. (Compare this with the much older, shorter U.S. Constitution with only 27 amendments.)

Things were different in 1876. The only citizens allowed to vote were adult white males who were not in prison or mental institutions and they wee the ones who wrote the constitution.

Endemic to their status was the desire to maintain control and influence. To do that, they would have to be able to determine who would be the governing officials at the local level. That meant they would have to be subject to regular retention or replacement through the ballot.

The governing officials, of course, would come from their ranks. Back then, females were not only denied the vote, they were considered incapable of managing a public office.

So requiring the male county sheriff, county clerk, and other county officials to stand for election every few years was no problem. For those in the voting ranks, politicking was easy and cheap. Candidates just had to contact other white males in their respective districts. That could be done by visiting the beer halls and other male hangouts, attend a few church picnics or other events held to showcase the candidates, and talk to the men.

There were no radio or TV ads to buy. Mailing campaign brochures was unheard of. The only real expenses for a political campaign were the filing fees, the costs of a few beers, and the feed for the horses needed to transport the candidates from place to place to visit with other men.

Time, though, marched on. Gender is no longer the overriding qualification for public office and any adult who is not in prison or in a psychiatric hospital can vote. Voters are now hidden in every nook and cranny. Just visiting male hangouts to solicit votes would no longer be a winning strategy.

Among the other changes of time were the growth of radio and TV advertisement and the replacement of horses and buggies with gas guzzling vehicles. Using these methods to contact, court, and cajole voters is not cheap. In a hotly contested race for a countywide office, those costs could exceed one year’s salary for the office being sought.

The cost to salary ratio is even larger for statewide and districtwide offices. In many races, campaign costs exceed the salaries for the entire term of the office being sought.

Even very wealthy men and women who want to serve and who could easily pay all their own expenses solicit campaign assistance from voters both in and outside their districts. This has become an acceptable method of vote or influence buying.

Is this an assault on representative government? Does every voter have equal access to their elected officials, or do campaign contributors get preferential treatment?

Regardless of the answers to those questions, there is no apparent way to curb the exorbitant costs of political campaigns. Any attempt to limit the amount of money that can be spent on a campaign by either an office seeker or his/her supporters would be struck down as an assault on free speech.

So here’s the perspective.

The march of time buried the ability of adult white males to control governments through the ballot boxes that existed in 1876. The same changes have imposed a heavy financial burden on political office seekers.

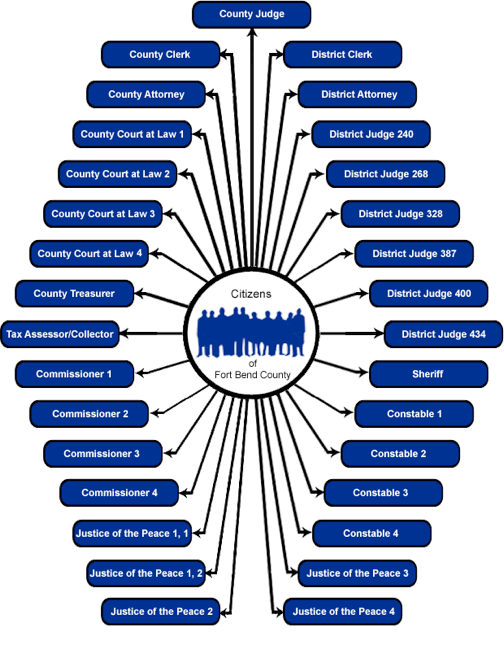

The only apparent solution to that burden for county officials in Texas is reorganization. Changing county government to a city manager type arrangement would not adversely affect county business. Such a change, however, would shorten the ballots. This, in turn, would reduce the flood of campaign literature descending on voters every two years.

Currently, county offices created by the 1876 constitution are filled by election but recent creations are filled by appointment.

The best example of this anomaly may be the establishment of property values for taxation. Originally, that was done by County Tax Assessor/Collectors who were and are elected officals. Today that is done in County Appraisal District offices. The Chief Appraiser is hired, not elected.

Does electing one and appointing the other make sense?

enough